Distance is relative. What may seem like an unbreachable distance to one may be nothing to another in different times and circumstances. When my third-great-grandfather Archibald Cole was mortally wounded in the Battle of Petersburg on 17 June 1864, as far as he and his family were concerned, he might as well have been on the moon. Week 5’s theme is “so far away”, and I could not think of a better example than Archibald Cole.

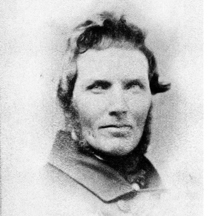

Archibald Lamont Cole was not a young man when he enlisted in the Second Michigan Infantry. He was born 28 January 1816 in the town of Western in Oneida County, New York, the sixth of eight children born to John Cole and Jennett Lamont. In 1839, at age 23, he moved to Jackson County, Michigan with his father, and shortly thereafter married his first wife, Elizabeth Lane, and had three children, Arthur, Eveline, and Isabelle, before Elizabeth died in 1848. In 1854, he married his second wife, my third-great-grandmother Mary Ann Townsend, and had four more children: Leonard Townsend, Irwin (who died before age two), Winfield William, and Elizabeth, my second-great-grandmother.

On March 28, 1864, Archibald was approached by a recruiter for the Second Michigan Infantry looking for men to fill a new company. In a letter written on 10 October 1889 to an old military friend, Dr. J. W. Stone, a former sergeant of Company D of the 2nd Michigan, wrote:

“I wrote to Leonard T. Cole [oldest son of Archibald and Mary Townsend], of Canton, N.Y., regarding his father who was a member of Capt. Stevenson’s Co. D. in 2d Mich. Inf. I remember him well. Capt. Ricaby was raising his Co. in Hillsdale and sent me to Albion to recruit some men. In those days men were getting scarce and I returned with only one man, Archibald T. [sic] Cole. He was a middle-aged man then and full of patriotic feeling. I remember how he talked to me, that he had stayed out of the service of the country too long but it did not seem as if he could leave home before or even now. He had a quiet dignity about him that made us all respect the man and when we got to the front and were assigned to Co. D, the old veterans of the company soon learned to respect Cole for his few words and his constant presence in the company.”

Archibald Cole was also much older than the typical recruit — in fact, older than they wanted, with three children at home all under ten years of age. in 1864, Archibald was 48 years old, although his enlistment papers and all subsequent military records list his age as 42. All his civilian records, including the family Bible where I obtained his birth date, all agree with his 1816 birth. Early in the Civil War, military units were taking men for as few as three to six month enlistments, sure the war would be over in short order. However, later in the war, most military enlistments were for a minimum of three years, including the 2nd Michigan. Although I have not been able to confirm this fact, I have talked to several Civil War experts who said that many units would not take men if they would be older than a certain age by the end of their enlistment period, and it stands to reason that the 2nd Michigan may have stated that they would not take men who would be older than 45 when their service ended. This would explain why Archibald would declare himself as 42, which is likely the youngest age he could reasonably expect to sell.

Sadly, Archibald’s military career was extremely short. J.W. Stone and Archibald Cole returned to the 2nd Michigan just as they were headed toward the tumultuous Second Battle of Petersburg in Petersburg, Virginia, 700 miles from his home in Albion, Michigan. 17 June 1864 was “a day of uncoordinated Union attacks”, including a charge from the 2nd Michigan:

“…when after the fearful charge of the old 2d across the corn field on the afternoon of June 17, 1864 … I found [Archibald] sitting leaning against a tree, waiting for the carriers to take him to the surgeons, who were already busy …. Among it all I remember Cole’s telling me in his quiet way that it was all up with him. He knew that his wound would be fatal but it was for the old flag and it was all right. I think I wrote a letter for him, or got one written. I know I promised to see his family but when years after I was in Albion I could find nothing of them.”

By 20 June 1864, Archibald was transported by train to a military hospital in Washington, D.C., having taken a Minie ball to the chest.

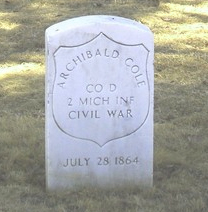

Nearly two weeks after his injury, on 1 July 1864, Archibald Cole died of his wounds and was buried in a newly-opened military cemetery on the outskirts of the city. By this point in the war, most of the capitol’s cemeteries were full to bursting. In a nose-thumbing gesture to Gen. Robert E. Lee, they appropriated the grounds of property belonging to his wife to create a new cemetery, originally for common soldiers such as Archibald whose families were too poor to pay to have their remains shipped home for burial (at this time, this was the financial responsibility of the families). By war’s end over 4,000 Union soldiers had joined him under plain wooden markers, most of which rotted to unreadability, so years later when the government finally financed permanent markers, they could only positively identify about 1/4 of the soldiers buried there. In an unusual stroke of genealogical luck, Archibald Cole was identified, even though his marker has the wrong date of death (which, as a direct descendent, I can apply to have fixed. Filing the proper paperwork is one of my planned projects this year).

Archibald Cole’s grave marker. The unit and company are right, but the date is off by almost a month.

The cemetery is now known as Arlington National Cemetery, after the name of the estate belonging to the family of General Lee’s wife, Mary Custis Lee. Creating a cemetery on the mansion’s grounds was intended to make the mansion undesirable for anyone from that Confederate family to reclaim, although they didn’t count on her determination. Shortly after the end of the war Mary Custis Lee began the bitter fight to reclaim the mansion and have the bodies removed from the grounds, but in 1870, Congress voted overwhelmingly to deny the home and grounds’ return. The fight had one major effect: it elevated the status of Arlington from a burying ground of indigent soldiers to one of the most prized and prestigious pieces of real estate for the dead in the United States.

There is no evidence Mary Ann Townsend Cole came to Washington D.C. to be with her husband in his final days; likely she did not even find out about his death until after it was over. I could not find the exact prices of trains in 1864, but it was almost certainly well out of reach of a young farmer’s wife with three small children.

Family line: Archibald Cole (1816-1864) and Mary Ann Townsend (1833-1868); Elizabeth Cole (1861-1927) and Theodore Frank Snyder (1861-1905); Ruth Adele Snyder and William Marcus Curtis; William Curtis and Helen Austin (my paternal grandparents).