Tags

England, Hampshire, Kenyon, Maternal, Oades, Portsmouth, Southampton, Sweetingham

I have a very, very good reason for missing Week 8 of this challenge: I was “across the pond” doing genealogy research. The theme for Week 9 was even fitting for telling this story; I was not close to my home, but I got the rare opportunity to do overseas genealogical research somewhere that was close to the home of my ancestors: Southampton, Hampshire, England. These are the relatives who, by 1820, were living in Sackets Harbor, Jefferson, New York, which is also my own hometown.

My fifth-great-grandparents were John Oades, a shipwright, and Lucy Sweetingham, both born in Hampshire, England. They are from my mother’s side of the family, related to my Kenyon lines. Until last week, this was nearly all I knew about them, beyond some of their siblings and the names of their parents.

John was born in 1786 in Southampton, to Thomas Oades and Mary Frost and was baptized at St. Mary’s Church, a church that dates back to a Saxon structure when the area was still known as Hamwic, about the year 634. When John was baptized there on Christmas day, 1786, the church was on the fourth renovation (it’s been renovated a total of six times); today all that remains of that iteration of the church happens to be the baptistry, since much of the church was destroyed during the blitz in November 1940. John had three sisters (Elizabeth, Charity, and Mary) and two brothers (Henry Frost and Thomas).

St. Mary’s Church, Southampton. This is not what the church would look like today; all but the tower, bells, and baptistry (small area on the left) were destroyed in the Blitz in November 1940.

Lucy Sweetingham was born 1787 in Southampton, to Hugh Sweetingham and Elizabeth Strugnell. She was baptized on 28 December 1787 at St. Leonard’s church in Bursledon, which is just outside Southampton to the east. Lucy came from a very large family; I have found at least eight brothers and three sisters, although at least one of the brothers died at a very young age.

John and Lucy were married at the parish church in Hound (just south and west of Bursledon) on 25 February 1811, and had three of their six children in Bursledon: Mary (b. 1811, six months after her parents’ wedding), John (b. 1815), and Elizabeth (b. 1817). Around 1818, the family moved to America, first for a couple years in New York City, and then to Sackets Harbor, Jefferson, New York, where John took up his profession as a shipwright.

Why John left for America is still something of a mystery, but learning some things about the climate for work in that area helped put some of this in perspective. The early 1810s were a busy time for shipbuilding in Southampton, as it was one of the major naval shipbuilding yards, and between war with America and war with France, there was plenty of work for shipwrights. However, after both wars ended by 1815, there was a major scaling back of shipbuilding, and thus work dried up quickly. There began to be a lot of discussion on how to bring back the shipbuilding industry, with the focus seeming to go primarily toward the development of steamships capable of handling the more inland waters of the Rivers Hamble and Itchen, as well as the Southampton waters. John Oades build sailing ships, and that’s not where the direction of shipbuilding was going. My guess here is that he went for the reasons many people chose to leave: follow the work.

There is a story that John Oades had a Canadian land grant in reward for his service to the British government, but there is some reason why I doubt this story. I discussed this with the maritime experts at the Southampton city archives, and they agreed with me that this would not have been any kind of usual procedure to reward a shipwright. Shipwrights were rarely formally connected with the British Navy; they worked primarly for private firms or as today’s equivelant of an independent contractor. Only shipwrights or ship’s carpenters assigned to sail out with a particular vessel were officially government workers — and when that meant the British Navy at the time, that was generally a lifetime assignment. What is not in doubt is that there was “a” John Oades who does have record of a land grant in Canada, which is something I plan to look up, but if there is one thing that I learned while I was over there is that John was an exceptionally common name in the Oades family. It’s not clear to me that the John Oades who received the land grant was “my” John Oades. My own research does not indicate that he and his family ever lived in Canada.

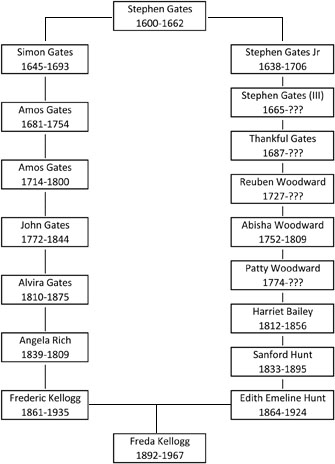

I was able to trace the Oades family back to my ninth-great-grandparents, John and Margarett Oades. The Oades family goes back as follows:

John Oades and Lucy Sweetingham (5th ggp)

Thomas Oades and Mary Frost (6th ggp)

Thomas Oades and Elizabeth May (7th ggp)

Thomas Oades and Charity Foster (8th ggp)

John Oades and Margarett — (9th ggp)

What I learned that did surprise me about the Oades family is that they are somewhat recent to Southampton itself. John Oades’ father was the first to arrive in Southampton. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all from Portsmouth. I know for certain that his father Thomas was also a shipwright; I was not only able to discover that he had been apprenticed by indenture to become one, but also found the name of his master (John Bissell) and even the name of the ship for which John Bissell was the master carpenter (the H.M.S. Modeste – yes, it has a Wikipedia page). In addition to Portsmouth, many of the Oades family was also in Winchester.

In fact, my actual Southampton connections are limited only to John Oades and his father. His grandmother May’s relations were also in Portsmouth. Lucy’s Sweetingham family was from Bursledon since the early 1700s, but prior to that was in Alverstoke and Gosport (near Portsmouth), although her Strugnell mother’s family seems to have been in Bursledon as far back as the records go. Her grandmother was a Phillips and her great-grandmother was a Plowman, and both families were from Eling, just across the Southampton water. They were never far from shipbuilding activities and never far from the waters north of the Isle of Wight and the English Channel.

It was a little surreal, standing in places where my relatives worked, went to church, possibly had a pint (two of the pubs I ate in have been in business since the 14th century and are located near the old dockyards), knowing that I may be the first of John and Lucy Oades’ progeny to return to the home soil.

The Duke of Wellington pub was just past the Western Quay and the old docks, near the city wall and about a three minute walk from my hotel. It’s gone through several names; by John Oades’ time it would have been known as the Shipwright Arms and primarily served the shipbuilders. I ate a magnificent fish and chips and toasted the memory of my own shipbuilders’ past with Talisker Storm scotch. Fitting, really.